A Summer Homily About Humility

J. R. R. Tolkien starts The Lord of the Rings with 75 pages of maps, family trees, the history of middle earth, and other prologue about hobbits and their different clans, and finally an extended chapter about a birthday party.

To this day, if you read reviews on Reddit or Google books, there’s always a few who criticize Tolkien for such a long wind-up. They want him to cut to the chase and get straight to the battles, monsters, and romances.

But Tolkien defended his opening, insisting that unless you knew something about the languages, the geography, and the history, you can’t understand his story.

I agree. If we don’t tell a story in the right context, we risk projecting our own bias into the story, and missing the point.

I used to teach a class on the theology of marriage and courtship at Villanova. One day a student wrote an essay comparing the portrayal of marriage in Tolkien’s books versus Peter Jackson’s movies. As great as the movies are, my student’s careful comparison shows how tone deaf the movies are to some of the backstory and indeed Tolkien’s deep Catholic instincts. The humility of the hobbits, or the romance between the human king Aragorn and the elven princess Arwen, come across quite differently in the books and the films.

I mention all this because all four of today’s readings are preoccupied with the relationship between Jews and Gentiles, between Israel and the Church. Paul, a Jew, in today’s passage from Romans, says directly “I am speaking to you Gentiles,” and so we Gentiles are the intended audience for today’s scriptures. But to understand these scriptures, to get Jesus right, we have to respect the ancient Jewish context and embrace Israel’s history as our history.

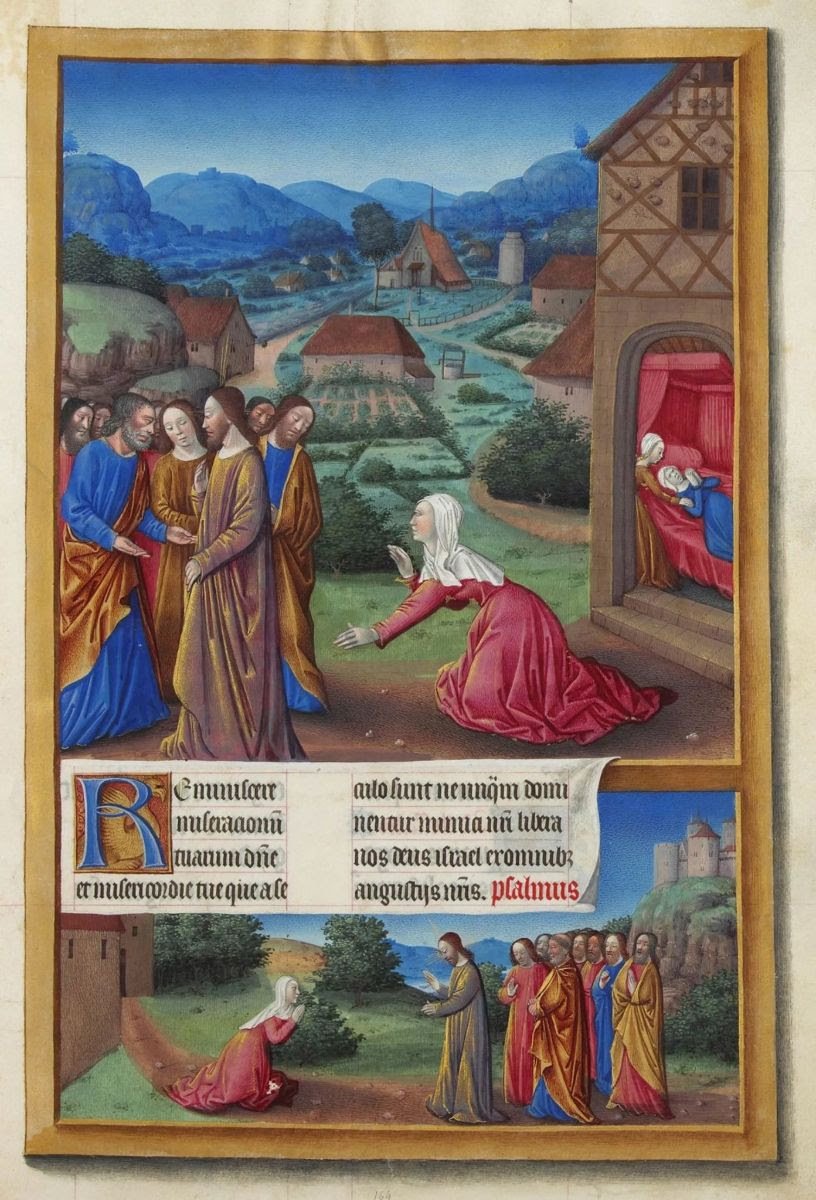

The Canaanite woman in today’s Gospel is our proxy. She and we are Gentiles. We have no right or entitlement to be God’s covenant people – we’re admitted not on the basis of our race, class, or gender, but by his grace and mercy. The response that Jesus asks from us is confession, humility, love, and faith.

The Gospel opens by saying Jesus withdrew to the region of Tyre and Sidon. Just as with Tolkien’s maps, geography is a clue. Tyre and Sidon are miles and miles away from Jesus’ central focus in Galilee. Tyre and Sidon are Gentile, pagan regions. For Jesus to be there is a signal about his intended audience.

Then the woman is referred to as being Canaanite. Now at the time of Christ, “Canaan,” as a land and as a people, had already been extinct for centuries. It’s an anachronism, an out-of-date way of referring to a place or a person. My wife is from England; it’s as if I called her an Anglo-Saxon. Fr. John’s family is from Ireland; it’s as if I called them Hibernians.

So why call her a Canaanite? Because the word is signaling that the woman is from Israel’s ancient foe. She’s not just any old Gentile, but she is really, super duper, mega un-chosen. You could not imagine an identity more outside the covenant.

And then she speaks: “Have pity on me, Lord, Son of David! My daughter is possessed by a demon and I need help.” She addresses him as Lord. She appeals to his Jewish royal lineage. Something very unexpected is happening: even though she is an outsider, she is paying homage to Israel and to Jesus’ supernatural authority.

Now we can debate what happens next. How Jesus reacts to the woman can be interpreted in different ways. He is silent at first. He lets the disciples take the lead, and they ask him to send her away because they’re sick of her persistence. Jesus appears to double down on their prejudices, to call this Gentile woman a dog.

But here’s another clue that something different is happening deep down. The word that Jesus uses for “dog” is diminutive, perhaps a touch affectionate, as if he’s calling her a puppy. It could still be an insult, but I imagine Jesus winking at the lady as he says it, signaling to her while reeling the disciples into a trick. The disciples are probably like “yeah, right, see…he’s calling this Canaanite a dog, ha ha.” But it’s a set-up, because he’s going to turn the tables on their prejudice. He embraces this “dog.” He claims the “dog” as one of his own people. “Great is your faith, o woman” (humanizing her), and her daughter is healed.

Now at this point, some modern readers might be tempted to think the moral of the story is clear. We can pat ourselves on the back for being more enlightened and inclusive than those parochial disciples. But that would be a mistake, projecting our own politics back into scripture. Yes, Jesus is inclusive, with a heart open to the marginalized, but if we left it at that, we would overlook how the marginalized woman has her own agency as well.

In this story, neither Jew nor Gentile get a prize simply by virtue of their identity. The Canaanite woman is favored because she confesses three times that Jesus is Lord. She prays to him as Son of David, as King of Israel. She steps forward on behalf of her daughter, not herself. She takes the supernatural and demonic seriously and asks for deliverance, inviting Jesus to intervene in her family. She addresses Jesus from a place of humility and reverence rather than entitlement.

Friends, God loves everyone, and everyone is invited to join his people. God’s love reaches out to the margins, and has a special place for all the oddballs, all the lonely, all the quirky Canaanite equivalents. We too should have hearts that are alert and wide open.

But, for us to claim our own identity, to step forward as beloved children of God, to receive God’s blessings and to know his love alive and blazing in our hearts, the Canaanite woman is an example we should follow. As we continue with this Mass and walk forward to receive this Eucharist, like the Canaanite woman, we defer to Jesus as Lord, we confess his rule and our humility. We invite him as the authority into our families, and we confess that we enter into God’s covenant not by right, but by his mercy and gift.